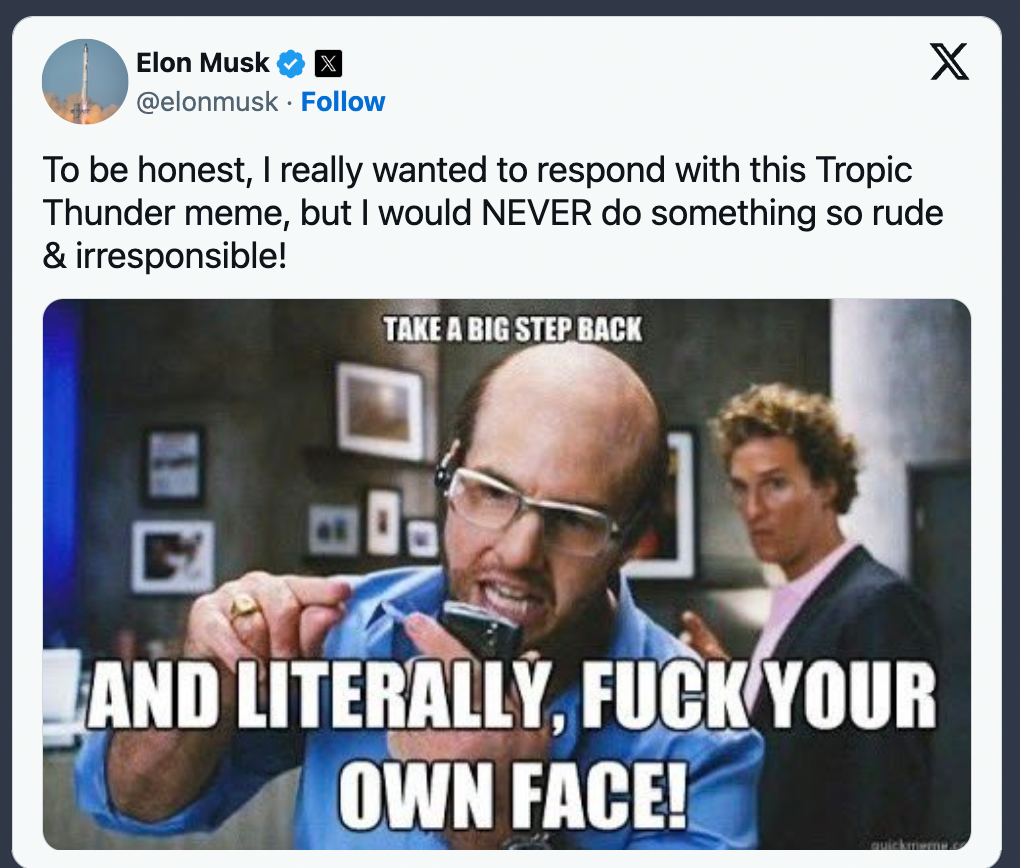

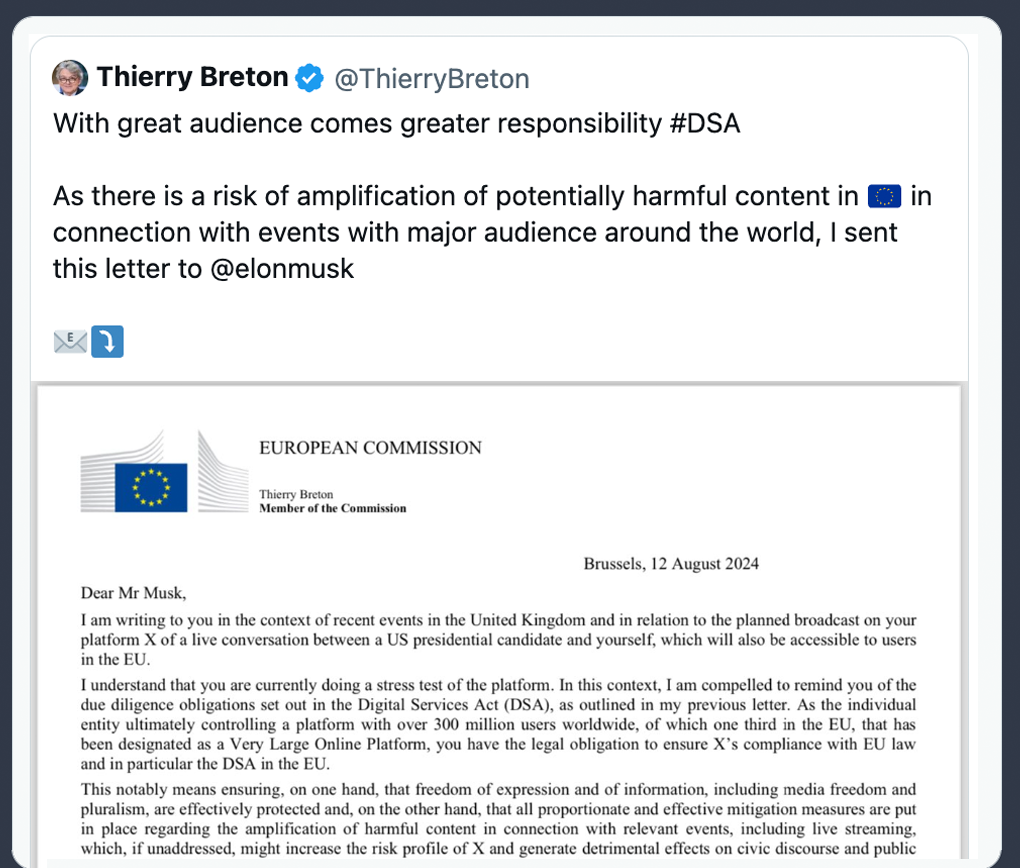

About one year ago, the EU Commissioner Thierry Breton sent Elon Musk a formal letter about X’s legal obligations under the Digital Services Act. Musk’s response? A vulgar meme telling Breton to “fuck your own face”, served up to nearly 200 million followers.

Think about that for a second. A tech billionaire told a European Commissioner representing 450 million people – to go screw himself. Publicly. Crudely. With zero consequences. No fines appeared. No diplomatic crises erupted. The meme landed, people shared screenshots, and everyone moved on.

While Elon Musk’s response sure was childish and disrespectful, above all it exposed an uncomfortable truth: where power in the digital age really lies. Spoiler: not in Brussels.

The moment crystallized a deeper truth about Europe’s position in the digital world. As Brussels is currently negotiating with the Trump administration over the AI Act, Digital Services Act (DSA), and Digital Markets Act (DMA), a profound irony emerges: Europe seeks to regulate the very technologies upon which it has become existentially dependent. The clash between the EU’s regulatory ambitions and the USA’s aim to deregulate under the banners of “freedom of speech” and “freedom from ideology” reveals more than just ideological differences.. It exposes a fundamental power imbalance that threatens the very essence of European democracy.

While civil society justifiably keeps pushing for stronger EU negotiation positions to uphold legal frameworks, the real challenge isn’t about regulations. It’s about power. European public discourse remains fixated on crafting better rules and stronger enforcement mechanisms, missing the fundamental reality: you cannot regulate what you do not control.

This article explores how European digital dependency has created a sovereignty paradox that undermines its democratic foundations: From German military forces relying on Google’s cloud infrastructure, to Elon Musk’s open contempt for European institutions, to the quiet but growing dependence on Chinese-built 5G networks and platforms like X, Instagram or TikTok shaping Europe’s public sphere.

We examine how the digital realm has become a new frontier of power where traditional notions of sovereignty no longer apply. Ultimately, the real challenge for European democracy is not whether Europe can uphold its laws to govern American tech giants, but whether it can break free from the dependencies that render those laws meaningless.

The Regulatory Mirage: When Laws Meet Reality

Europe has crafted an impressive arsenal of digital regulations: the GDPR, the AI Act, the DSA, and the DMA represent the most comprehensive attempt to govern the digital realm democratically. Yet, these laws exist in a curious vacuum, regulating technologies that Europe neither controls nor truly understands. It is as if a nation tried to regulate the sea while living entirely on borrowed ships.

The contradiction becomes striking when we examine Europe’s actual digital infrastructure. In April 2025, Germany’s armed forces (the so-called Bundeswehr) announced a major cloud computing contract with Google, choosing American technology for its most sensitive military operations.1 While officials defended this as an “air-gapped” solution, the underlying reality remains unchanged: Europe’s military depends on foreign technology controlled by a nation increasingly hostile to European values.

This dependency extends beyond military applications into the heart of European law enforcement. Several German federal states including Bavaria, Hesse, and North Rhine-Westphalia rely on Palantir’s “Gotham” surveillance software, a system not only developed by a company with deep ties to American intelligence services.2 Behind Palantir stands Peter Thiel, a billionaire investor whose profile is as influential as it is dubious. Known for funding anti-democratic projects and fostering networks hostile to liberal values, Thiel embodies how foreign private actors can gain leverage over the very institutions meant to protect European democracy.3 The irony is profound: European police forces use American surveillance tools to monitor European citizens, creating a digital panopticon where the watchers themselves are watched by foreign powers.

And it is not only the United States: Europe remains heavily dependent on Chinese technologies, particularly regarding hardware for information and communication technologies (ICT) and the rollout of 5G networks. Suppliers like Huawei and ZTE continue to play a central role in components for mobile networks and data centres, embedding Chinese infrastructure deep into Europe’s digital backbone. In both security and the public sphere, foreign technologies have become embedded at the core of European democracy.4

These are not isolated incidents, but symptoms of a deeper structural dependency. Europe finds itself in a paradoxical position: politically sovereign, yet structurally dependent on foreign technologies. This asymmetry raises a haunting question for European leaders, one that regulation alone cannot resolve: how can democratic standards be safeguarded when the very technologies they rely on may ultimately undermine them?

The New Political Infrastructure: When Platforms Replace Parties

The implications of this digital dependency extend beyond technical considerations. Social media platforms have quietly replaced traditional political parties as the primary infrastructure of democratic discourse. They determine what information citizens see, which voices are amplified, and how political movements organize and mobilize. In this new landscape, platform owners have become unelected kingmakers with the power to shape democratic outcomes.

Nowhere is this more evident than in the actions of Elon Musk, whose ownership of X has transformed him into a shadow political actor across European democracies. An Associated Press analysis revealed that Musk has systematically amplified far-right figures across Europe, effectively acting as a “kingmaker” in European politics.5

His support for Germany’s AfD party, including hosting a livestream with party leader Alice Weidel weeks before a major election, represents unprecedented foreign interference in European democratic processes. In the UK, far-right activists, including some involved in controversial actions and even legal sentences, benefited from Musk’s amplification, gaining up to nearly a million new followers after Musk’s engagement on X.6

Meta’s actions have been equally corrosive to European democratic processes, though more subtle in their execution. The company’s decision to cease all political advertising in the EU, citing transparency rules as “unworkable,” effectively reduces electoral transparency while claiming to protect free speech.7 Simultaneously, Meta’s elimination of fact-checking programs in favor of user-driven “community notes” creates fertile ground for disinformation and foreign manipulation.

Equally concerning is TikTok, the Chinese-owned platform that now reaches nearly 170 million monthly users in the EU.8 For many young Europeans, it has become the primary source of news and culture. Its algorithmically-curated feeds don’t just shape entertainment trends but increasingly political discourse – creating the possibility of subtle influence on elections and public opinion. The EU has already launched investigations into TikTok’s impact on democracy, citing opaque algorithms, viral misinformation, and the platform’s growing role as a new arena for foreign soft power. 9

These platforms have fundamentally altered the nature of political power. Traditional democratic institutions such as parliaments, political parties, or civil society organizations find themselves competing for attention and influence with algorithms designed to maximize engagement rather than democratic participation. The result is a political landscape where outrage travels faster than truth, where foreign actors can influence domestic politics with unprecedented ease, and where the very infrastructure of democracy serves interests antithetical to democratic values.

The Sovereignty Paradox: Regulating Without Power

This brings us to the heart of Europe’s dilemma: the sovereignty paradox. Europe possesses the legal authority to regulate digital technologies, but lacks the technical capacity to enforce its will. It is a regulator without teeth, a sovereign without power over its own digital realm.

The current situation reveals the limitations of traditional regulatory approaches in a digitally interconnected world, as laws and regulations assume a relationship between sovereign authority and territorial control that no longer exists in cyberspace. When European regulators threaten fines or sanctions, American tech companies can simply withdraw services, leaving European citizens and institutions dependent on technologies they cannot replace.

This dependency creates a vicious cycle. The more Europe relies on American digital infrastructure, the less leverage it has to regulate American companies. The less it can regulate, the more dependent it becomes. Each new contract with Google, each deployment of American software in European institutions, each reliance on American platforms for democratic discourse deepens this dependency and weakens European sovereignty.

The Trump administration’s threats of sanctions against European officials implementing digital regulations represent the logical endpoint of this dynamic.10 When foreign governments can threaten European officials for enforcing European law, the pretense of sovereignty becomes difficult to maintain. Europe appears politically in charge, yet in practice it remains dependent on decisions made far beyond its own borders.

Pathways to Digital Resilience

Breaking free from this digital dependency will require more than regulatory reform – it demands a fundamental reimagining of Europe’s relationship with technology. Several pathways offer hope for reclaiming democratic control over the digital realm.

European Platform Infrastructure: Perhaps the most urgent priority is breaking free from American and Chinese social media platforms whose algorithms remain beyond European control and whose owners – as Elon Musk’s earlier mentioned contemptuous response illustrated – refuse meaningful collaboration with European institutions. The irony is striking: Europe plans to invest billions of Euros in traditional defense capabilities while focusing almost exclusively on conventional warfare, ignoring the sphere of information and cognitive warfare that has been threatening European societies for more than a decade.

The battle for European democracy is not being fought with tanks and missiles, but predominantly with algorithms and engagement metrics. Building European alternatives to Facebook, X, TikTok, and YouTube is nothing less than a democratic necessity. These platforms must be designed with European values at their core: transparency, accountability, and democratic governance rather than engagement maximisation and profit extraction. If Europe truly wants to safeguard its democratic future, it needs to be in control of what happens in its digital public sphere, applying its own mechanisms for content moderation and algorithmic amplification.

The EuroStack Vision: The most ambitious solution lies in the EuroStack initiative, a comprehensive plan to build European digital sovereignty from the ground up.11 This “moonshot” project envisions a complete European digital ecosystem: from semiconductors and cloud infrastructure to artificial intelligence and quantum computing. With an estimated investment of €300 billion by 2035, EuroStack would give Europe the technological independence necessary to enforce its democratic values in the digital realm.

The initiative recognizes that digital sovereignty cannot be achieved piecemeal. Just as the creation of the euro required comprehensive monetary infrastructure, digital independence demands a complete technological stack under European control. This includes not only the visible applications, but the underlying infrastructure, cables, servers, and algorithms that form the nervous system of digital society.

Digital Resilience and Democratic Participation: Alongside technological independence, Europe must champion a new concept of “digital resilience”, the idea that citizens should have meaningful participation in how digital technologies are designed and deployed. This goes beyond privacy rights to encompass democratic participation in technological governance. Citizens should have a voice in algorithmic design, platform policies, and the fundamental architecture of digital society.

Strategic Procurement and Market Creation: Europe can accelerate its digital independence through strategic procurement policies – a “Buy European” approach that prioritizes European technologies in public sector contracts. This would create guaranteed markets for European tech companies, helping them achieve the scale necessary to compete with American and Chinese branch giants. When European governments and institutions commit to European solutions, they create the economic foundation for technological sovereignty.

Digital Diplomacy and Alliance Building: Finally, Europe must recognize that digital sovereignty is not a zero-sum game. By building alliances with like-minded democracies and promoting open standards and interoperability, Europe can create a democratic alternative to the current duopoly of American and Chinese digital hegemony.

The Choice Before Europe

Europe stands at a crossroads that will shape the future of democracy in the digital age. The choice is stark: to remain dependent on foreign powers for the very infrastructure of democratic life, or to take the harder road towards digital sovereignty and genuine self-determination.

The stakes could not be higher. In an age where information is power and algorithms shape reality, control over digital infrastructure is control over democracy itself. To outsource this control to foreign actors – particularly those with demonstrated hostility to European values – is to surrender the essence of democratic sovereignty.

The path to digital liberation will be long, costly, and politically demanding. It will require unprecedented cooperation among European nations, massive public investment, and the courage to place long-term sovereignty above short-term convenience. Yet, the alternative is far more dangerous: a future in which European democracy is shaped not by the laws it enacts, but by the infrastructures it does not control.

It’s time to rethink the future we’re building.

References

Header Image generated with Adobe Firefly

- Knop, D. (2025). Bundeswehr relies on Google Cloud. Heise Online. https://heise.de/-10397526

- Fürstenau, M. (2025, August 2). German police expands use of Palantir surveillance software. Dw.com; Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/german-police-expands-use-of-palantir-surveillance-software/a-73497117

- Raphaëlle Bacqué, Leloup, D., & Alexandre Piquard. (2025, July 22). Peter Thiel, the libertarian billionaire waging war on government. Le Monde.fr; Le Monde. https://www.lemonde.fr/en/summer-reads/article/2025/07/22/peter-thiel-the-libertarian-billionaire-waging-war-on-government_6743617_183.html

- Deutschlandfunk. (2025, July 3). Digitalisierung – Europa im globalen Wettrennen um Souveränität. Deutschlandfunk. https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/digital-strategie-europa-unabhaengig-usa-china-chips-clouds-100.html

- Rankin, J. (2025, January 8). EU Commission urged to act over Elon Musk’s “interference” in elections. The Guardian; The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/jan/08/eu-commission-urged-to-act-elon-musk-interference-elections

- Macaskill, A., Marshall, A. R. C., & Carey, N. (2025, March 4). Musk rallies the far right in Europe. Tesla is paying the price. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/musk-rallies-far-right-europe-tesla-is-paying-price-2025-03-04/

- Chan, K. (2025, July 25). Meta will cease political ads in European Union by fall, blaming bloc’s new rules. AP News. https://apnews.com/article/meta-instagram-facebook-eu-european-union-political-89efeac96723308d2a0469740d24d433

- Dredge, S. (2025, September 3). TikTok and Instagram reveal latest user numbers in the EU. Music Ally. https://musically.com/2025/09/03/tiktok-and-instagram-reveal-latest-user-numbers-in-the-eu/

- Hahne, S., & Haas, F. (2024, December 17). EU leitet Überprüfung ein: Wahlerfolg mit TikTok? Tagesschau.de. https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/europa/tik-tok-rumaenien-wahl-eu-100.html

- Pamuk, H. (2025, August 26). Exclusive: Trump administration weighs sanctions on officials implementing EU tech law, sources say. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/us/trump-administration-weighs-sanctions-officials-implementing-eu-tech-law-sources-2025-08-26/

- Bertelsmann Stiftung. (2021, July 15). EuroStack – A European Alternative for Digital Sovereignty. Bertelsmann-Stiftung.de. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/eurostack-a-european-alternative-for-digital-sovereignty