An uncovered protest in Geneva, a censored keynote, and a booming multi-billion dollar market.

Have you heard about the protest accompanying the AI for Good Summit? No? Well, you’re probably not alone. Personally, I only learned about it through my personal network, some of whom attended the summit and reported about the following incidents. Thanks, social media!

In July 2025, while the United Nations’ AI for Good Global Summit was underway in Geneva, a small group of protestors gathered at the iconic Broken Chair monument. They were protesting the summit’s sponsorship by major tech companies, particularly Microsoft, Amazon, and Google, whose technologies are increasingly integral to AI in warfare and modern military operations. The protest highlighted a fundamental contradiction: the same corporations promoting “AI for Good” are simultaneously profiting from its use in global conflicts.1Strikingly, no European major media outlet covered the protest.

Inside the summit, this tension reached a boiling point. The keynote by Dr. Abeba Birhane – a leading scholar on algorithmic bias – turned into a striking example of the limits of “ethical AI” discourse. The livestream was cut off the moment she began to critique the use of AI in the Gaza conflict. According to Dr. Abeba Birhane, organisers pressured her at the last minute to remove slides referencing the war in Gaza as well as the logos of Microsoft, Amazon, Google Cloud, Palantir, and Cisco under the heading “No AI for War Crimes”.2

The incident, which Dr. Birhane and others present3, described as a deliberate act of censorship4 sent a worrying message: even at a forum dedicated to the ethical development of AI, critical discussions about its military applications are being suppressed. While the International Telecommunication Union (ITU), as the event’s organiser has neither confirmed nor denied the incident, Meredith Whittaker – president of Signal and a widely recognised authority on AI – was present and corroborated it publicly.5

Was this censorship motivated by her critique of AI warfare, or by her critique of Israel’s actions in Gaza? In practice, the distinction hardly mattered. What was clear was that the organisers intervened on two fronts: references to geopolitics and direct criticism of Big Tech Companies. This suggests the issue was not only geopolitical sensitivities but also the protection of sponsors with military contracts, whether tied to Gaza or to other conflicts.

The role of AI in warfare is probably one of the most pressing debates of our time – precisely the kind of debate we urgently need to have, not silence. It can save lives, but it can also endanger them. The usual framing goes like this: if AI is used by the “good guys”, it is acceptable; if used by the “bad guys”, it is a threat. But reality rarely allows the distinction into merely “good” or “bad”.

What actually drives war and peace are competing interests. Traditionally, these belonged to the warring parties themselves and specialized defense contractors: Lockheed Martin, BAE Systems, Rheinmetall – you name them. But with conflicts becoming increasingly digitalized, something fundamental has shifted: Tech companies have entered the military-industrial complex. Microsoft, the company that runs your email and wants to organize your life; Google, where you search for dinner recipes and store your photos; Amazon, where you buy Christmas gifts and stream your movies – have become the backbone of modern warfare.

This creates a fundamental problem: when profit becomes a driver of warfare technology, it directly conflicts with the goal of peace.

The controversy at the UN’s AI for Good Global Summit reveals a troubling truth: as we debate the ethics of artificial intelligence, its use in warfare is rapidly accelerating, funded by the very companies championing its potential for good.

This article examines the massive investments fueling this new arms race, why they threaten not only ethics but also the prospects for peace, and what it will take to ensure that AI for Good does not become a footnote to a future defined by autonomous conflict.

Big Tech’s $47 Billion in U.S. Defense Contracts

While the world debates the ethics of AI weapons, the companies building them are reporting record profits.

The numbers tell the story. Global military spending hit $2.46 trillion in 2024 – a 38.9% jump since 2018,6 and tech companies are grabbing an ever-larger slice of this pie.

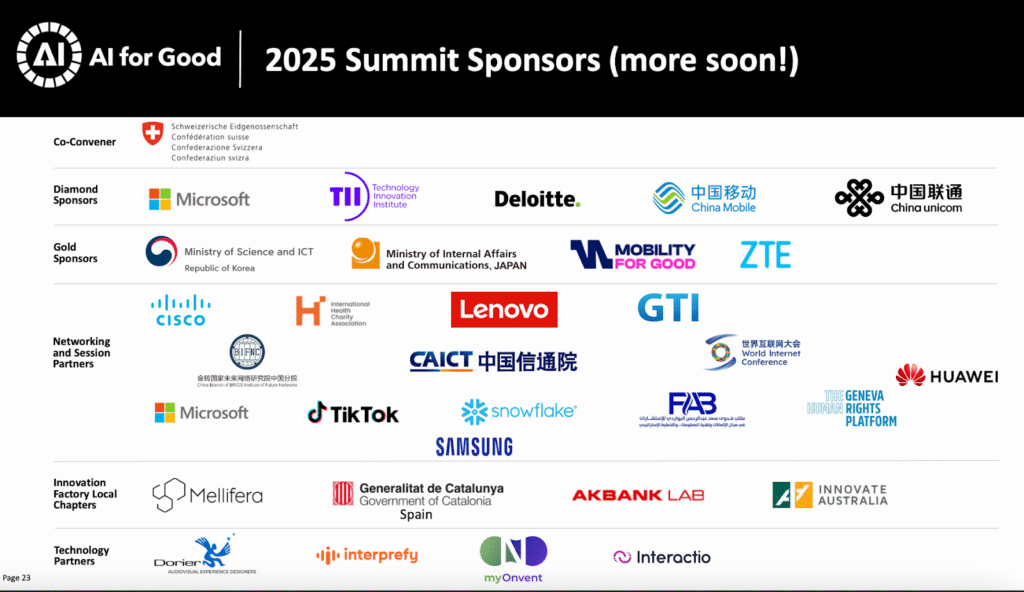

Screenshot from the AI for Good sponsorship Brochure

Seven key sponsors of the AI for Good Summit – Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Oracle, Palantir, IBM, and Cisco – hold a combined $47.7 billion in active U.S. defense contracts.7 These are the same companies we use for email, cloud storage, and search engines.

Microsoft‘s $22 billion contract to supply the U.S. Army with its Integrated Visual Augmentation System shows how consumer tech becomes military tech.8 Amazon‘s AWS cloud division handles $10 billion worth of National Security Agency contracts and $600 million for the CIA.9 Even Google, which publicly withdrew from Project Maven in 2018 after employee protests, quietly re-entered with a $200 million AI contract for the Pentagon’s AI office.10

The U.S. Department of Defense alone has tripled its AI-related contracts, from $190 million before August 2022 to over $557 million recently.11 However, this represents just the visible tip of a much larger iceberg that includes classified contracts, international sales, and the broader ecosystem of subcontractors and suppliers.

The companies that sponsor the AI for Good initiatives are the primary beneficiaries. The deep integration of the tech industry with the military-industrial complex creates powerful incentives that push for the continued development and deployment of AI in warfare, often with little regard for the ethical implications. When your business model depends on conflict, peace becomes a threat to revenue. And, as the lines between “big tech” and “big defence” continue to blur, the goal of AI for Good is at an increasing risk of being undermined by the logic of military competition and commercial interests.

When Peace Becomes Bad for Business

Unlike traditional arms manufacturers, companies developing military AI gain not only from sales but from the conflicts themselves. Most military strikes now generate valuable operational data, and a significant share of this information is used to iteratively train and refine AI systems for targeting, navigation, and decision-making. In conflicts like Ukraine, for example, targeting results, sensor data, and battlefield conditions feed machine learning models, improving recognition and flight paths. Each strike becomes training data, refining AI accuracy and decision-making over time.12

This exposes a structural flaw: when profit becomes a driver of warfare technology, it directly conflicts with the goal of peace. We can see this playing out in three troubling ways. First, tech companies now have financial incentives to develop increasingly lethal AI systems and expand their military applications – not because it makes conflicts more ethical, but because it makes them more profitable. Second, this profit motive is driving the suppression of critical debate about these technologies, as we witnessed with Dr. Birhane’s censored keynote. Thirdly, it shifts the authority over questions of war and peace away from peace experts into the hands of tech specialists, sidelining those who actually study how peace can be achieved.

Of course, there are broader concerns that go beyond profit motives – the erosion of meaningful human control, algorithmic bias in targeting, and the accountability gap when autonomous systems kill civilians. But those debates, while urgent, are a different discussion. What matters here is the structural perversity introduced by Big Tech’s profit model.

Every strike generates new datasets that improve algorithms, making war both a battleground and a laboratory. The more the violence escalates, the more sophisticated the algorithms become. Peaceful resolution means less data, slower improvement, and reduced competitive advantage.

This creates what economists call a “perverse incentive structure”. Companies developing military AI have financial reasons to prefer:

- Longer conflicts over quick resolutions: Longer wars mean more data. Extended timelines secure multi-year contracts, while constant updates keep revenue flowing.

- Expanding conflicts over containment: New war zones demand new AI tools. Each expansion multiplies profits and turns conflicts into live sales demos.

- Automated warfare over human-mediated solutions: Autonomy cuts labour, boosts dependence. More data and premium pricing make full automation the most profitable path.

This poses a crucial challenge to peace: if companies profit from the digital traces of war, peace itself turns into a liability.

Breaking the Profit–Peace Trap

The AI for Good Summit made one thing clear: reputation laundering is no substitute for real accountability. But it also revealed something even more troubling: we’re caught in a profit-peace trap where those with the most power to change the system benefit most from keeping it broken.

The summit’s sponsor list reads like a who’s who of military AI contractors. The $47.7 billion in U.S. defense contracts they hold exposes the scale of this contradiction.

What makes this particularly troubling is not just the sponsorship, but the silence. Critical debates – such as the use of AI in the Gaza Strip – are systematically pushed off the agenda. But, when uncomfortable truths are excluded, the promise of AI for Good becomes little more than a branding exercise.

Tech companies have become part of a structural perversity: they profit both from selling military AI technology and from the conflicts themselves, through the data each strike generates.

Breaking this cycle starts with acknowledging that today’s gatekeepers of AI ethics are compromised. As noted in the introduction, reality rarely allows us to divide neatly between good and bad. The same holds true here: the companies mentioned above are not inherently “evil”, but their profit structures make peace the losing side. Their sponsorship of AI for Good-initiatives may appear constructive, yet the underlying structural problem remains: war is profitable, peace is not. Until this incentive structure changes, until cooperation becomes more valuable than conflict, AI for Good will remain what Geneva revealed it to be: well-intentioned rhetoric constrained by economic reality.

It’s time to rethink the future we’re building.

For a broader data-driven analysis of how #AIForGood compares to economic deployments, see AI for Good or AI for Growth?

References

Header Image generated with Adobe Firefly

- Donmez, B. B. (2025). Protest in Geneva Slams AI for Good Summit over Big Tech’s Reported Role in Gaza War. Aa.com.tr. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/europe/protest-in-geneva-slams-ai-for-good-summit-over-big-techs-reported-role-in-gaza-war/3625487

- Birhane, A. (2025, July 10). AI for Good [Appearance?]. AI Accountability Lab. https://aial.ie/blog/2025-ai-for-good-summit/

- Derja, A. (2025, July 14). I Sat Through Geneva So You Don’t Have To. Substack.com; Asma’s Substack. https://asmaderja.substack.com/p/i-sat-through-geneva-so-you-dont?r=46hjev&utm_medium=ios&triedRedirect=true

- Goudarzi, S. (2025, July 10). AI for good, with caveats: How a keynote speaker was censored during an international artificial intelligence summit. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. https://thebulletin.org/2025/07/ai-for-good-with-caveats-how-a-keynote-speaker-was-censored-during-an-international-artificial-intelligence-summit/

- Arseni, M. (2025, July 10). UN AI summit accused of censoring criticism of Israel and big tech over Gaza war. Genevasolutions.news; Geneva Solutions. https://genevasolutions.news/science-tech/un-ai-summit-accused-of-censoring-criticism-of-israel-and-big-tech-over-gaza-war

- Liang , X., Tian, N., Lopes da silva, D., Scarazzato, L., Karim, Z., & Ricard, J. G. (2025). Trends In World Military Expenditure, 2024. https://www.sipri.org/sites/default/files/2025-04/2504_fs_milex_2024.pdf

- Own Analysis of defense contract data from USASpending.gov, company SEC filings, and government contract announcements.

- Nellis, S., & Dave, P. (2021, April 1). Microsoft wins $21.9 billion contract with U.S. Army to supply augmented reality headsets. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/technology/microsoft-wins-219-billion-contract-with-us-army-to-supply-augmented-reality-idUSKBN2BN36B/

- Gregg, A. (2021, August 11). NSA quietly awards $10 billion cloud contract to Amazon, drawing protest from Microsoft. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/08/11/amazon-nsa-contract/

- Conger, K., & Wakabayashi, D. (2021, November 15). Google Says It Can Compete for Pentagon Contracts Without Violating Principles. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/15/technology/google-ai-pentagon.html

- Henshall, W. (2024, March 27). U.S. Military Spending on AI Surges. TIME. https://time.com/6961317/ai-artificial-intelligence-us-military-spending/

- Ismail, K. (2024, November 19). Artificial Intelligence in Military Conflict: Critical Reflections. Next Century Foundation. https://www.nextcenturyfoundation.org/artificial-intelligence-in-military-conflict-critical-reflections/

The urge for power and money is a general thing. We have entered a time where conflicts are all around us, so it is obvious that a business model must be created to benefit from it. Although the article reveals – in a very revealing way – this uncomfortable truth, my sarcastic side is not surprised.

What is exciting is that you write “when profit becomes a driver of warfare technology, it directly conflicts with the goal of peace “. This brings me to the following philosophical question: if that is the case, doesn’t that mean we have to create more value for peace, compared to warfare?

Dear Stefan, thank you very much for your comment, i am glad to know the article is resonating with you. I believe you are pointing right to one of the most important questions of our time, and in my opinion this does not only count for peace, but also for other “social goods” such as education, health care, care work, etc.