In 1992, when the World Wide Web was still in its infancy, visionary author Neal Stephenson wrote the groundbreaking science fiction novel Snow Crash. Decades before “avatars” and “metaverse” became tech buzzwords, Stephenson’s vision of a 3D virtual reality—the “Metaverse”—offered a glimpse into the future, where users navigate a digital cityscape as avatars, much like we browse today’s websites and social media.

The metaphor of the Internet as a bustling metropolis captures the diversity of our digital landscape’s communities and spaces—some fostering collaboration and free exchange of ideas, others breeding conflict and misinformation. The novel’s central conflict—a virus threatening the Metaverse’s stability—powerfully illustrates the challenges we face in maintaining digital peace.1

As the Internet has become an integral part of our daily lives, urgent questions about our current digital environment arise: How do we protect our interconnected world from the “viruses” of hate, misinformation, and conflict? The need for approaches that promote “digital peace” is more urgent than ever. But what exactly does “digital peace” mean, and how can we achieve it?

In this article, we’ll explore the limitations of current approaches to regulating cyberspace. Following up on our last posts, where we discussed the manifestations of online threats in our daily lives, and the impacts of digital violence, we’ll delve into the root causes of online conflict and propose a more comprehensive framework for achieving digital peace.

Current Approaches and their Limitations

In its early days, the internet embodied the hope for a new digital future—one defined by connection, collaboration, and cross-cultural understanding. This exciting yet utopian prospect imagined a digital realm where people could freely share their stories and ideas, forging connections across cultures, bridging divides, and empowering communities to advocate for justice and understanding in a truly democratic environment. While idealistic, this vision embodied the very essence of digital peace—an online world promoting inclusivity, mutual respect, and global harmony.

However, the evolution of the digital landscape has been somewhat different than expected. New challenges—such as information and cognitive warfare, cyberattacks, data breaches, and privacy violations, among others—emphasize that achieving digital peace requires more than the original vision of openness and connectivity.

In response to these growing digital threats, governments and international organizations have implemented various initiatives aimed at safeguarding the online space. At the forefront of these efforts, national governments, often supported by international organizations like NATO, now treat cybersecurity as a crucial operational domain.2 This shift has led to significant investments in systems designed to detect and respond to attacks, ensuring the safety and integrity of vital digital infrastructures. A key tool in shaping these efforts is the development of National Cyber Strategies (NCS). Typically led by government agencies responsible for national security, these strategies help nations navigate the complexities of international cyber policy while protecting their own digital assets.3 Given the private sector’s dominance in cutting-edge technologies and data resources, governments increasingly rely on private companies for advanced security systems, data analytics, and strategic communications.

Beyond cybersecurity, we are witnessing increasing collaboration between governments and technology companies in the fight against misinformation. With external actors increasingly using disinformation and propaganda to manipulate public opinion, discussions around “Foreign Information Manipulation and Interference” (FIMI) have surged in recent years. FIMI includes disinformation, misinformation, and propaganda attempts by foreign state actors to influence public sentiment through traditional and digital media. To counter this, fact-checking initiatives, content moderation systems, and counter-influence campaigns have become essential tools in mitigating the effects of disinformation.4

To further govern the digital space, many nations have introduced regulatory frameworks. Digital governance, requiring international cooperation, has led to collaborative standards such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which has set a global example for data protection and platform accountability. Other notable collaborations include the African Union’s Malabo Convention on Cybersecurity and Data Protection, ASEAN’s cybersecurity frameworks, and several United Nations initiatives, such as the recently established convention against cybercrime.5

While these measures address immediate digital threats, they tend to be reactive, focusing on harm prevention after incidents occur. Consequently, these efforts, while necessary, often fail to address the deeper systemic issues that give rise to such threats. Without addressing the root causes of conflict, there remains a risk of perpetuating a cycle of digital violence.

Systemic Issues and Root Causes of Digital Violence

To create lasting digital peace, it’s essential to go beyond surface-level solutions and examine the more complex, foundational challenges that drive conflict in the digital world. Beyond immediate threats like cyberattacks and disinformation, the digital ecosystem faces a series of systemic issues and deep-rooted causes of violence that need to be addressed in order to break the cycle of digital conflict.

1. Systemic Issues in the Digital Ecosystem

In order to foster a safer and more inclusive digital environment, we must confront the underlying systemic issues that often escape immediate attention but significantly shape the nature of online interactions:

- Undemocratic power structures in tech: The creation and governance of our digital world is dominated by large tech companies, often surpassing the influence of governments and leaving citizens with little say. This unequal distribution of power in shaping online environments undermines digital democracy and inclusive participation.6

- Digital exclusion: Unequal access to technology and digital literacy skills creates power imbalances and limits diverse participation in online spaces.7

- Algorithmic bias: AI-driven content curation and recommendation systems can inadvertently amplify divisive content or reinforce existing prejudices, distorting public discourse.8

- Surveillance capitalism: The extensive collection and monetization of personal data erodes trust, manipulates user behavior, and almost entirely commodifies digital interactions, ultimately undermining user experience and digital well-being.9

- Echo chambers: Social media algorithms that prioritize engagement can trap users in ideological bubbles, hindering exposure to diverse viewpoints.10

- Online radicalization: Subtle psychological tactics employed by extremist groups can gradually pull vulnerable individuals towards harmful ideologies.11 0What aspects are you missing here?x

2. Root Causes of Digital Violence and Information Warfare

In addition, online violence is rarely isolated from broader societal conflicts. More often than not, it reflects deeper geopolitical tensions, social inequalities, and ideological divisions. To effectively combat digital violence and information warfare, we must recognize digital conflicts as extensions of larger struggles.

For example, gender inequality and ethnic tensions frequently manifest in digital spaces, where marginalized groups become the targets of harassment and hate speech. Similarly, long-standing geopolitical conflicts are mirrored in information warfare, as state and non-state actors weaponize disinformation to exacerbate divisions.

While factors like power imbalances, echo chambers, and algorithmic amplification contribute to digital violence, the root of the problem often lies in deeper socio-political and economic disparities. These conflicts, now playing out in the digital realm, make achieving digital peace an immense challenge.

To move forward, we must integrate traditional peace-building approaches into the digital space while also developing new strategies that address the underlying conflicts driving digital warfare. This means fostering dialogue between opposing factions, promoting mutual understanding, and working toward cooperation on a global scale. Only by addressing these root causes can we hope to create a truly peaceful and stable digital environment.

The Three Pillars of Positive Digital Peace

In 1969, Johan Galtung, widely recognized as the father of peace and conflict studies, published his groundbreaking article “Violence, Peace, and Peace Research” in the Journal of Peace Research.12 This seminal work extended the conventional definition of peace as the mere absence of violence, to introduce the concept of “positive peace”. Galtung’s framework, which distinguishes between ending conflict (negative peace) and building a sustainable, just, and inclusive peace (positive peace) while highlighting the often-overlooked cultural and structural dimensions of violence, remains a critical reference for scholars and practitioners.

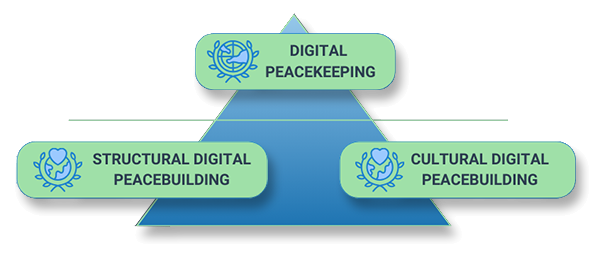

Adapting these concepts to the digital age, we identify three key dimensions of digital peace: Digital Security, Structural Digital Peace, and Cultural Digital Peace. This approach reflects Johan Galtung’s conflict triangle. Digital Peacekeeping addresses immediate threats and hostile actions, focusing on behavior. Structural Digital Peacebuilding addresses systemic inequalities and infrastructural challenges, in line with Galtung’s emphasis on underlying contradictions. Cultural Digital Peacebuilding fosters respectful and empathetic norms, reflecting the attitudinal component of Galtung’s model, which is essential for sustaining long-term peace.

Triangular Framework of Digital Peace: Behavioral, Structural, and Attitudinal Dimension – Adapted from Galtung (1969)

1. Digital Security / Negative Digital Peace

This dimension encompasses the mitigation and elimination of direct forms of digital violence, including cyber attacks, misinformation propagation, online harassment, and hate speech. The primary objective is to foster a secure and protected online ecosystem. This aspect can be conceptualized as Digital Peacekeeping with Cybersecurity emerging as a central theme. The overarching aim is to maintain stability and security in the digital domain. Implementation efforts in this dimension include:

- Counter Influence Campaigns aiming to safeguard public discourse

- Cybersecurity measures implementing practices, technologies, and strategies to protect digital systems, networks, and data from threats, ensuring their confidentiality, integrity, and availability

- Fact-checking collaborations between tech companies, governments and international organizations

- Removal of harmful content

- Regulations to prevent the spread of false information

- Regulations on online violence, such as laws against cyber-bullying and digital harassment, and holding perpetrators accountable.

2. Structural Digital Peace

This dimension addresses systemic issues in the digital ecosystem, promoting equitable digital access and opportunities for users to shape their digital environments. It tackles the deep-rooted problems outlined above, such as undemocratic power structures in tech, digital exclusion, algorithmic bias, and surveillance capitalism, aiming to create a just, inclusive, and safer digital landscape. Activities within this dimension fall under Structural Digital Peacebuilding, focusing on establishing conditions for sustainable peace in the digital realm by addressing these underlying inequalities and challenges. Key initiatives include:

- Implementing inclusive, democratic decision-making processes in the management and development of online spaces and emerging technologies

- Digital rights advocacy campaigns targeting tech governance and data privacy

- Community-driven digital infrastructure projects to combat digital exclusion

- Inclusive and ethical design in technology development to mitigate algorithmic bias

- Collaborative online platforms that promote diverse viewpoints and counter echo chambers

- Digital literacy programs to empower users against online manipulation and radicalization

3. Cultural Digital Peace

This dimension focuses on cultivating online norms and values such as respect, empathy, and mutual understanding, building digital communities that promote peaceful interactions. Cultural Digital Peacebuilding recognizes that online violence often mirrors broader societal conflicts, including geopolitical tensions, social inequalities, and ideological divisions. The web can serve as a powerful tool for initiatives that enhance community cohesion and promote respect for diverse viewpoints. However, the digital world can’t be isolated from the offline world when it comes to fostering peace. Consequently, Cultural Digital Peacebuilding must work in unison with offline efforts in education and community development. It should therefore be reinforced by traditional peacebuilding initiatives, such as deconstructing hate and biases, fostering reconciliation, promoting mutual understanding, engaging in processes of dealing with past conflicts, and facilitating dialogue and mediation between conflicting parties. Key efforts include:

- Peace-promoting content

- Peace education for media literacy

- Online conflict resolution platforms

- Cross-cultural virtual exchange initiatives

- Ethical AI development and implementation

- Integration of digital and traditional peacebuilding approaches

Building peace in the digital realm, much like in traditional conflict resolution, requires a comprehensive approach that addresses immediate violent behaviors, underlying structural issues, and the cultural attitudes that sustain peace. In our new digital reality, these efforts must combine both online and offline measures, as sustainable peace can only be achieved by connecting digital initiatives with real-world social, political, and cultural solutions. Only by integrating these interdependent components can we create a robust framework capable of effectively addressing the complex challenges of fostering sustainable peace in the digital age, just as Galtung’s model suggests.

Building a Holistic Approach to Digital Peace

The Digital Landscape offers exciting opportunities for peacebuilding initiatives. Social media and technology can amplify diverse perspectives on conflict and give voice to local peacebuilders and grassroots efforts. Additionally, the emerging field of “Peacetech” explores how technological innovations can support peacebuilding, from simple communication tools to complex data analysis systems.

While there are many promising initiatives aiming to promote digital peace across the various dimensions outlined earlier, they often lack a coherent, structured, and institutionalized approach. Additionally, these efforts struggle to gain traction in an algorithm-driven economy that prioritizes sensationalism and conflict-centered narratives. Furthermore, Hirblinger et al. (2022) note a “fetishisation” of digital innovation in peacebuilding, with a disproportionate prioritisation of internet-derived data over direct engagement, potentially marginalising participatory methods and the voices of conflict-affected communities.13

The fragmented and uncoordinated nature of digital peacebuilding efforts starkly contrasts with the more cohesive approaches seen in cybersecurity and military strategic communications. While military and defense institutions are vital in responding to immediate digital threats, achieving lasting digital peace demands far more than counter-influence campaigns and technological solutions. It requires a comprehensive approach, where digital governance frameworks and peacebuilding initiatives are implemented effectively and collaboratively. These efforts must be concerted, inclusive, and grounded in democratic principles to ensure a truly peaceful and resilient digital ecosystem.

Consequently, achieving positive digital peace hinges on the grassroots involvement of communities, individuals, and civil society in the promotion of a culture of respect, empathy and mutual understanding online. Top-down initiatives can set the stage by creating frameworks and guidelines, but it’s the bottom-up actions—educating users, promoting digital literacy, and encouraging positive online behavior—that will ultimately sustain these efforts. Together, these approaches can create a comprehensive strategy for achieving digital peace.

What can you do?

The future of digital peace starts with you. We can no longer rely solely on governments and tech companies to create a safer online world—each of us has the power to shape this digital landscape.

Here are some ways you can make a difference:

- Educate yourself about the risks of misinformation, digital threats, and online safety. Knowledge is the first line of defense.

- Practice empathy in your online interactions. Your words can build bridges or walls—choose wisely.

- Support initiatives that advocate for digital access and education, ensuring that everyone has a voice in our digital world.

- Be an advocate for policies that create a more equitable and inclusive internet. Your voice matters in shaping the future of technology.

How are you contributing? Share your thoughts on digital peace in the comments! How can we as individuals contribute to a more peaceful online environment? How much power should we really allow tech giants to have over our daily experiences? Can we truly achieve digital peace, or is conflict an inherent feature of the (online) world? Join the conversation below and be part of the movement for a peaceful digital future.

References

- Stephenson, N. (1992). Snow crash. Rizzoli.↩

- NATO. (2024). Cyber Defence. NATO. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_78170.htm?selectedLocale=en.↩

- Hofstetter, J.-S. (2024). The Future of Cybersecurity Policy Lies in Civil Society. https://ict4peace.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/The-future-of-cybersecurity-policy-lies-in-civil-society-2.pdf.↩

- EEAS Strategic Communication. (2024). Tackling Disinformation, Foreign Information Manipulation & Interference | EEAS Website. Www.eeas.europa.eu. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/tackling-disinformation-foreign-information-manipulation-interference_en.↩

- Runde, D. F., & Ramanujam, S. R. (2021). Global Digital Governance: Here’s What You Need to Know. Www.csis.org. https://www.csis.org/analysis/global-digital-governance-heres-what-you-need-know.↩

- Khanal, S., Zhang, H., & Taeihagh, A. (2024). Why and How Is the Power of Big Tech Increasing in the Policy Process? The Case of Generative AI. Policy & Society (Print). https://doi.org/10.1093/polsoc/puae012.↩

- Politische Medienkompetenz. (2017). Digital Divide: Bedeutung für die Politische Medienkompetenz. Politische-Medienkompetenz.de. https://www.politische-medienkompetenz.de/unsere-schwerpunkte/digital-divide/.↩

- Friis, S., & Riley, J. (2023, September 29). Eliminating Algorithmic Bias Is Just the Beginning of Equitable AI. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2023/09/eliminating-algorithmic-bias-is-just-the-beginning-of-equitable-ai.↩

- Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. Public Affairs.↩

- Arguedas, A., Robertson, C., Fletcher, R., & Nielsen, R. (2022). Echo Chambers, Filter Bubbles, and Polarisation: a Literature Review. Reuters Institute, University of Oxforx, The Royal Society. https://doi.org/10.60625/risj-etxj-7k60.↩

- NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence. (2016). Social Media as a Tool of Hybrid Warfare. Stratcomcoe.org. https://stratcomcoe.org/pdfjs/?file=/publications/download/public_report_social_media_hybrid_warfare_22-07-2016-1.pdf .↩

- Galtung, J. (1969). Violence, Peace, and Peace Research. Journal of Peace Research, 6 (3), 167–191.↩

- Hirblinger, A., Hansen, J. M., Hoelscher, K., Kolås, Å., Lidén, K., & Oliveira Martins, B. (2022). Digital Peacebuilding: A Framework for Critical–Reflexive Engagement. International Studies Perspectives, 24(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/isp/ekac015.↩